Our Stories

Men from the community of Akhiok, Easter Sunday 1928. Courtesy of the National Archives, Alaska Schools Album.

Imaken Ima’ut—From the Past to the Future

Museum staff members discuss the past 300 years of Kodiak history and the ways Alutiiq life changed. Created with support from the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

Created with support from the Institute for Museum and Library Services.

Learn More

This free eBook shares Alutiiq/Sugpiaq history from the time Alutiiq people arrived in the archipelago till the present.

These one-page lessons explore topics in recent Alutiiq/Sugpiaq history. Download a copy to continue learning.

Deep History

Archaeological finds suggest that ancient Alutiiq/Sugpiaq history (7500 to 250 years ago) can be divided into three cultural traditions – ways of living.

Ocean Bay Tradition – Kodiak’s first residents arrived at least 7,500 years ago, colonizing an environment warmer and drier than today. Archaeologists believe these people came from southwestern Alaska and were well-adapted to life along the coast. Like their descendants, they used barbed harpoons, chipped stone points, and ground slate lances to hunt sea mammals, delicate bone hooks to jig for cod, and large bone picks to dig for clams. Early residents probably lived in both skin-covered tents and oval, single-roomed houses with sod block walls.

Kachemak Tradition – About 4,000 years ago, Kodiak people began to focus more intensely on fishing, harvesting quantities of both cod and salmon. They developed nets to harvest large quantities of salmon, and slate ulus and smokehouses to process the catch for storage. Over time, the island’s population grew and filled up the landscape. By the end of the Kachemak tradition, people were trading for large quantities of raw materials from the Alaskan mainland. Antler, ivory, coal, and exotic stones were manufactured into tools and jewelry. Labrets, decorative plugs inserted in the face, became popular at this time, perhaps to signal the social ties of the person wearing the labret in a landscape where there was increasing competition for resources. The first signs of warfare appear in the Late Kachemak.

Koniag Tradition – About 800 years ago, fishing grew even more important as people harvested even greater quantities of salmon to feed their families and trade with neighbors. Related families began living together in large, multiple-roomed sod houses pooling resources and labor. Chiefs emerged, perhaps to organize labor. They led war and trading parties and hosted elaborate winter ceremonies to display their wealth and power, honor ancestors, and ensure future prosperity.

This way of living persisted until the final decades of the 1700s, when the arrival of Russian traders swept the Alutiiq into the global economy and irreversibly changed the culture.

Learn More about the Koniag Tradition

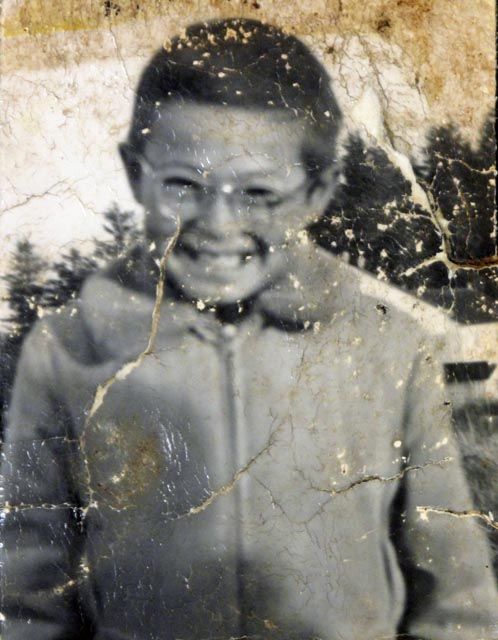

Daniel Harmon—Alutiiq Hero

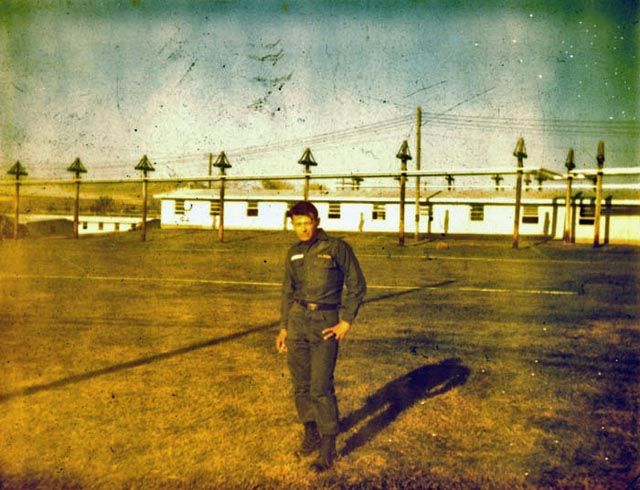

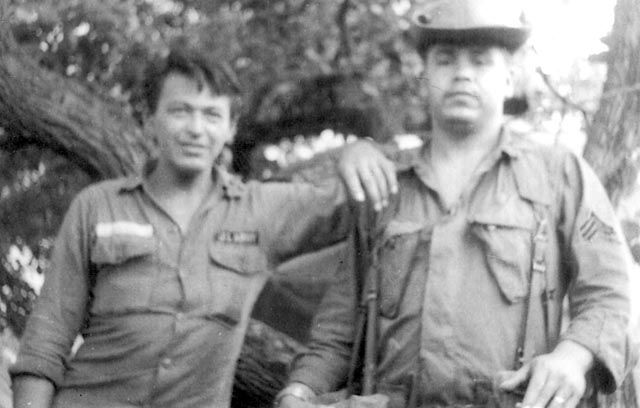

Daniel Harmon in Vietnam. Harmon Collection.

Native American people have served in every major American conflict since the Revolutionary War. Daniel Lee Harmon was an Alutiiq man from Woody Island, Alaska, who volunteered to serve his country by fighting in the Vietnam War. Throughout his tour of duty, Daniel showed courage and valor. At age 21, he made the ultimate sacrifice. Daniel was killed while trying to rescue a fellow soldier after helping another injured soldier to safety.

-

Childhood

Daniel “Dan” Lee Harmon was born on January 31, 1946. He grew up on Woody Island with his mother, Nettie, and eight siblings. Dan’s sisters, Rayna and Leanna, recall the simplicity and happiness of childhood on Woody Island. They played with rag dolls made by their mother, had picnics, went ice-skating, and enjoyed the beach. Dan ran all over the island, often rabbit hunting and fishing with his cousin, Fred Simeonoff. Dan was a skilled hunter and he provided a great deal of food for his family. -

Enlistment

As a young man living in Kodiak, Dan volunteered for the Alaska National Guard. During basic training at Fort Lewis, Washington, Dan spent weekends with family members living nearby. This included his brother, Mitch, and his niece, Margaret. They remember Dan’s big smile and his grin as he waved goodbye each Sunday when they dropped him back at Fort Lewis. Dan was known for his sense of humor and a smile that put people at ease. Despite Dan’s easygoing spirit, he was very serious about going to Vietnam. When he discovered his unit would not be sent to Vietnam, Dan went absent without leave (AWOL) for a day. He insisted on going, and in July of 1966, he began his tour.

-

Service

In February 1967, Harmon volunteered for the Army’s Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol (LRRP). He was assigned to the 2nd Brigade, 4th Infantry Division. When the 4th Infantry Division moved into Central Highlands of Vietnam in 1966, they became responsible for covering the largest, most remote and treacherous area of the country. Dan volunteered knowing the danger and he participated in numerous patrols, some involving ambushing small groups of opposing forces.

-

Bronze Starr

On a mission in February 1967, Dan was the radio operator on a four-man team. During their patrol the team located an enemy mortar squad and noted their movement toward a U.S. Infantry base. The team acted quickly, relaying the likely location of the enemy squad and the base bombarded the enemy position. The enemy squad spotted the Dan’s team. Dan summoned artillery support and accurately adjusted the position to provide them enough cover for a helicopter evacuation. For his actions, Dan received a Bronze Star for heroism.

In March 1967, on a patrol, Dan was wounded in both legs. His team left him behind, but he crawled to safety during the night. He was awarded a Purple Heart his the injuries.

-

Letters Home

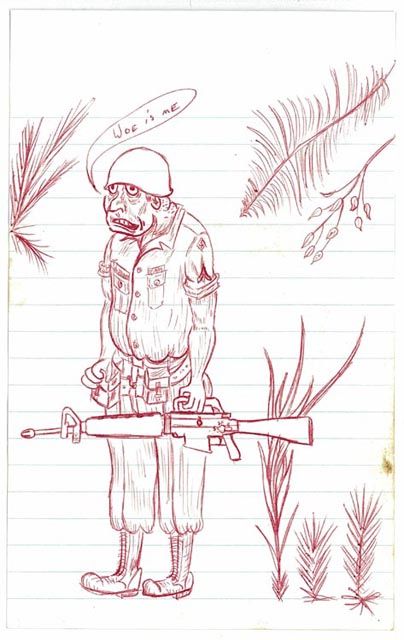

Dan’s letters to his sister, Leanna, reveal his sense of humor as well as his artistic abilities. Jim, Dan’s brother, remembers Dan’s drawings. He could replicate any illustration from a book and sketched on many of his letters home. From complete sketches to doodles, each picture shows his wit. In closing one letter, Dan drew a film reel using red ink and wrote, “The End – A Dan Harmon Production – in color – yuk-yuk.”

-

Final Battle

In late May 1967, Dan’s unit was ordered to carry out a damage assessment mission. Recently released from the hospital, and with just five days left of his tour, Dan volunteered to serve as the assistant team leader.

After spending the night in enemy territory near the Cambodian border, the team encountered a North Vietnamese Army squad and called for extraction. The Army deployed three tanks and an infantry platoon. As the tanks arrived, the team realized they were in the middle of a mine field. Enemy forces began detonating the mines damaging the tanks and injuring many. Harmon dragged a fellow soldier to safety and was attempting to save another when he was mortally wounded. He was 21.

-

Remembering Dan

In June 2003, family, fellow soldiers, and friends gathered on Woody Island to remember Dan. A Russian Orthodox memorial service honored Dan and his cousin Fred Simeonoff, a helicopter pilot who also died in Vietnam. Dan and Fred, both Alutiiq men, were the only two Kodiak casualties of the Vietnam conflict.

-

Recognition

During the week of the memorial service, fellow soldiers spent time getting to know Harmon’s family. In their conversations, they realized Dan had not been recognized for his actions. One of them spent three years gathering information and completing paperwork. Finally, in August 2007, over 100 people gathered at a memorial service to honor Dan, who was posthumously awarded a Bronze Star with the “V” device for Valor and oak leaf clusters – his third decoration.