Alutiiq Technological Inventory

Identifying Ancestral Tools

A 4,500-year-old slate lance found at the Kashevaroff site, Womens Bay, AM724.

For Native American people, whose history extends thousands of years beyond written records, objects are a very valuable source of historical information. Ancestral tools provide a window into distant times seldom available elsewhere. Sometimes, however, decoding that information can be difficult. The tools left behind are incomplete and very different from those used now.

This manual presents a summary of the tools Alutiiq/Sugpiaq ancestors made and used from about 7,500 years ago until the introduction of European tools. The manual groups ancestral tools by manufacturing method, to demonstrate how objects were created and the materials craftspeople employed. It is not a full accounting of Alutiiq technology, but a broad way to understand how Alutiiq ancestors transformed natural materials into implements for daily living.

Produced with a grant to Koniag from the Institute of Museum and Library Services. For questions about Alutiiq technology, please contact Patrick Saltonstall, 844-425-8844.

Manufacturing Techniques

Throughout history, Alutiiq/Sugpiaq ancestors transformed natural materials into essential tools. The materials people harvested and they ways they used those materials changed through time. Chapter 2 provides an overview of Alutiiq manufacturing and artistic traditions based on archaeological evidence from the Kodiak region.

Stone Working

In Alutiiq society, most tools were made from plentiful organic materials like wood, bone, and baleen. Every plant or animal harvested for food was also a potential source of material. Organic materials are not consistently preserved in ancestral sites, so many tools have been lost to decay. But some assemblages preserve carved and woven objects. As these tools are all made by carving, we have divided them into functional groups to help with identification.

Saw and snap slate grinding technique used by Alutiiq ancestors. Illustration by Eric Carlson.

Chipping stone is one of the oldest tool manufacturing techniques in the Kodiak region. Craftsmen used glassy cherts and volcanic rocks to shape tools with sharp cutting edges—knives, projectile points, scrapers, drills, wedges, and blades.

Photo. Chipped stone knife of basalt, Kashevaroff site, Am724.

Grinding is an effective way to shape soft stone or create a cutting edge. Alutiiq ancestors transformed leaves of slate into projectile points and knives by abrading the slate against another stone. They also ground coal, sandstone, quartz crystals, and other stones into objects.

Photo. Ground slate ulu with a bark handle, Karluk One, Koniag Collection.

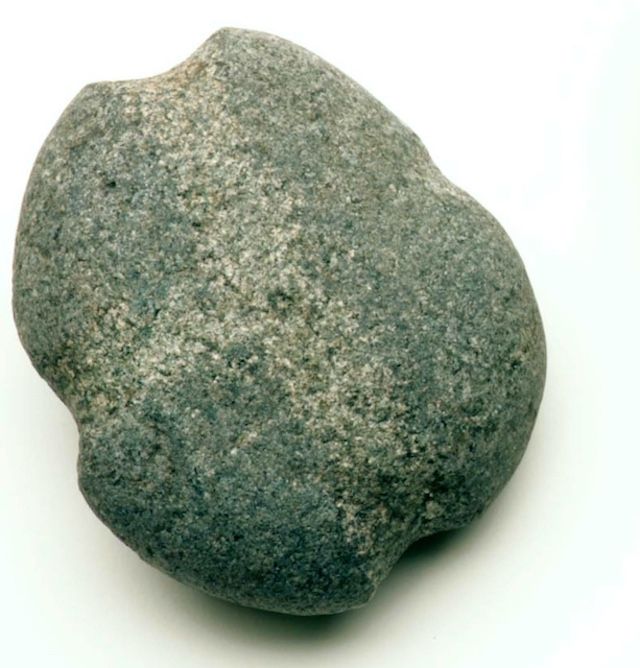

Alutiiq ancestors chipped and pecked water-worn cobbles collected from the beach to make lamps, sinkers, adzes, and many other tools. Many are made from Kodiak’s abundant greywacke and granite.

Photo: Line sinker for ocean fishing, greywacke, Karluk One, Koniag Collection, AM193.

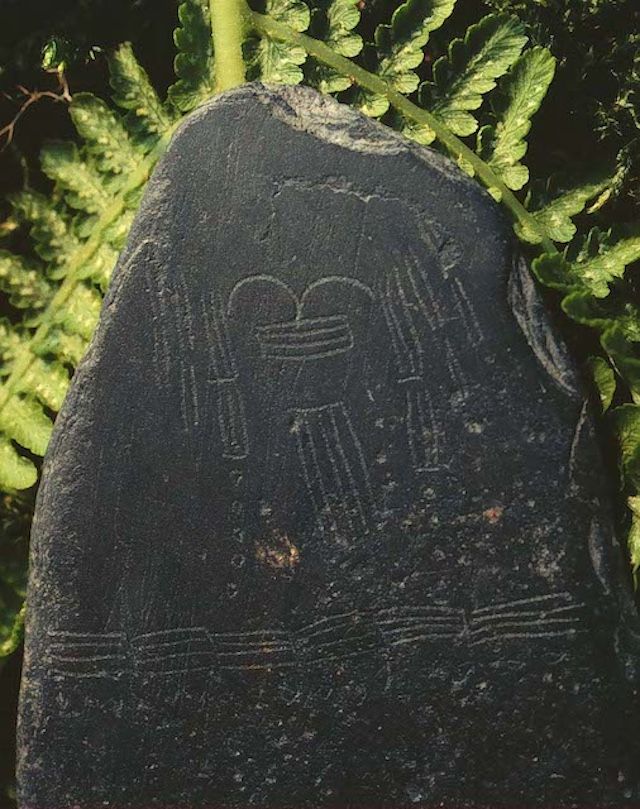

Many tools have incised designs—images or patterns cut into the surface. One type of object, an incised pebble is made entirely by incising. About 700 years ago, Alutiiq ancestors made hundreds of small pebbles etched with drawings of people.

Photo: Incised pebble, slate, Settlement Point site, AM33. Afognak Native Corporation Collection.

About 500 years ago, Alutiiq ancestors began making pottery from local clay tempered with sand and gravel. Large pots were probably used for melting sea mammal blubber to create oil.

Photo: Ceramic pot from Rolling Bay, Laughlin Collection, courtesy fo the Kodiak Area Native Assocaitin, AM50.

Worked Organics

In Alutiiq society, most tools were made from plentiful organic materials like wood, bone, and baleen. Every plant or animal harvested for food was also a potential source of material. Organic materials are not consistently preserved in ancestral sites, so many tools have been lost to decay. But some assemblages preserve carved and woven objects. As these tools are all made by carving, we have divided them into functional groups to help with identification.

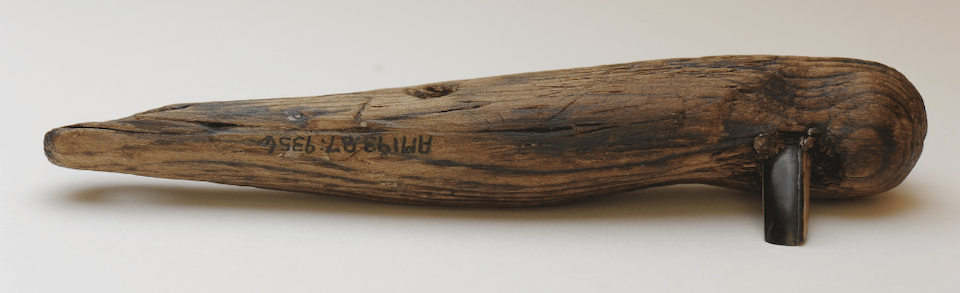

Ancestral carving tool with a marmot incisor, Karluk One site, Koniag Collection.

These tools were used for collecting and processing collected foods, particularly shellfish and plant roots. They are general-purpose tools that were likely used with collecting baskets (see Worked Fiber in Chapter 9).

Photo. Wood clam knives from Karluk One, Koniag Collection.

The carved tools in this group are associated with both marine and riverine fishing, including spearfishing for salmon in rivers, line fishing for cod and halibut in marine waters, and ice fishing with a lure and a leister. Many of these items are pieces of larger composite tools.

Photo. Antler and bone fish lures from Karluk One, Koniag Collection.

The carved tools in this group are associated with both marine and terrestrial hunting and trapping. They include some of the gear used by hunters as well as weaponry.

Photo. Antler and bone arrowheads from Karluk One, Koniag Collection.

The two major types of Alutiiq boats—qayat (kayaks) and angyat (open skin boats) are both large composite artifacts with many parts. For the purposes of artifact cataloging, we group parts by boat type.

Photo. Wood paddle blades from Karluk One, Koniag collection.

The objects in this class are associated with house building and large-scale woodworking. This includes the tools used in the initial stages of log reduction and plank making, as well as those used for digging foundations.

Photo. Wood wedges from Karluk One, Koniag Collection.

This category of tools includes items designed to aid the manufacture of tools and clothing.

Photo. Ivory grass comb, Clyda Christiansen Collection, AM679.

This category of tools includes fire-starting tools, containers, and tools used to prepare and hold food.

Photo. Bentwood box from Karluk One, Koniag Collection.

This group of tools includes objects commonly associated with steam bathing.

Photo. Wooden tools for the banya, Karluk One, Koniag Collection.

This group of objects includes items designed for children’s play—dolls, miniatures, and boat carvings.

Photo. Toy boats with figurines, made of bark, from Karluk One, Koniag Collection

This groups of tools features carved items associated with warfare.

Photo. Wooden shield fragment from Karluk One, Koniag Collection.

This group of objects includes items used in gaming (gambling), typically by adults.

Photo. Wooden Kakangaq disks from Karluk One, Koniag Collection.

This group of objects includes jewelry and objects associated with clothing decoration.

Photo. Wooden labrets from Karluk One, Koniag Collection.

The objects in this category are associated with the spiritual life of Alutiiq ancestors, including those used in personal rituals, shamanism, and winter festivals.

Photo. Wooden feast bowl from Karluk One, Koniag Collection.

Worked fiber objects are rarely preserved in Kodiak’s archaeological sites. However, a few sites have produced examples of woven, braided, tied, and sewn artifacts made from plant and animal tissues.

Photo. A fragment of baleen weaving, Kalruk One site, Koniag Collection.

Materials

Red chert outcrop at the entrance to Malina Bay, Afognak Island. Red chert is a chippable material Alutiiq ancestors used to make tools.

Alutiiq ancestors transformed a great variety of natural materials into tools—from beach cobbles and leaves of slate, to animal bone and shell. Some of these materials were locally abundant. Others came to Kodiak from the mainland. Identifying the origins of materials helps archaeologists understand the ways materials were used and study patterns of manufacture, trade, and travel.